Zarlasht Sarmast

Department Of Psychology, American University Of Central Asia

April 2023

Abstract

Afghan students at AUCA have always experienced trauma as a result of living in Afghanistan.

One of the events that was most traumatic is the withdrawal of the US military forces from the

country and the takeover of the Taliban in summer 2021. Prospective memory is a memory for

actions to be performed in the future, such as composing an abstract for Congress. Various studies

(for instance, Khan, A, 2020) showed that deficits in prospective memory are part of depressive

cognitive deficits. This study’s objective was to test the hypothesis of the existing connections

between traumatic stress symptoms and prospective memory. One hundred and thirty-two Afghan

students (39,9%) at AUCA submitted informed consent for participation in the study, which was

approved by the IRB of AUCA. The average age was 21.5 years old, (45%) male students, and

(55%) female students. The research was quantitative, PCL-5 was used to measure the level of

traumatic stress among Afghan students, along with the Cognitive failure questionnaire (CFQ),

Prospective Memory Concerns Questionnaire (PMCQ), and Remembering to do things (RDT).

There were found significant correlation between level of hyperarousal, and a score of RTDT

questionnaire (r= 0.351, p.001), also with the score of Cognitive Failures Questionnaire and

hyperarousal (0.336, r=0.001), and score of prospective memory questionnaire and the total score

of PCL-5 (r=.351, 0.001). There were also found significant differences between level of

hyperarousal in male and female Afghan students (p= 0.008), and avoidance (p.=0.01) ANOVA

also showed a significantly high level of self-reported cognitive failure among female students.

This study suggests that prospective memory deficiency is part of a traumatic cognitive deficit.

Key words: Afghanistan, AUCA students, post-traumatic stress, prospective memory, cognitive

failures.

Declaration

I declare that I clearly understand the American University of Central Asia’s essay, undergraduate

thesis and master thesis writing and anti-plagiarism rules and regulations. The submitted

dissertation is accepted by AUCA on the understanding that it is my own effort without

falsification of any kind. I declare that I fully understand that plagiarism is academically fraudulent

and against the AUCA rules and regulations. I declare that I am aware of the consequences of

plagiarism and cheating.

Name: Zarlasht Sarmast

Signature

01/31/2023

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Thanks to Dr. Elena Molchanova for supervising my thesis. Also, thanks to the American University of Central Asia for providing educational opportunities. With this, I appreciate and thank AUCA’s professors, staff, and the President.

Table of Contents

List of abbreviation definitions

Introduction

Literature review

Take away from the literature review

Purpose of this study

Research questions

Hypothesis

Recruitment

Instruments and Procedure

Results

Discussion

Future implications

Conclusion

List of recommendations for institutions who are working with students who faced traumatic experiences, lived in war zones and faced displacement

Appendix:

Literature citations and references

List of abbreviation definitions

- AUCA – American University of Central Asia

- AUAF – American University of Afghanistan

- OSUN – Open Society University Network

- OSF – Open Society Foundations

- U.S – United States

- PTS – Post Traumatic Stress

- PTSD – Post Traumatic Stress Disorder

- RTDT – Remembering To Do Things

- PM – Prospective Memory

- CM – Cognitive Memory

- CA – Cognitive Abilities

- APA – American Psychological Association

- GWoT – Global War on Terrorism

Introduction

Afghanistan and the citizens of Afghanistan considering what they have been going through during the last 40 years, offers a great source of studies and research for the sciences field, especially psychology. Afghanistan is a country where more than 60% of the population consists of youth. That means people who are between the ages of 15 – 27 years old (UNFPA Afghanistan, 2023). Taking this number into account and reflecting back on the situation in Afghanistan during the last 40 years, since the invasion of Soviet Union in December 1979 to February 1989, the first takeover of the Taliban in the 1990s, then the global war against terrorism (GWoT) and finally the continuous war between the U.S military forces and Afghan military forces against Taliban in the country (George W. Bush White House Archives. (n.d.). National Security Strategy documents. Retrieved April 17, 2023,), we can suggest that most youth born and raised between these years have experienced some form of traumatic events until now. This research’s main focus is on the community of Afghan students who were evacuated to Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan in August of 2021 for safety reasons.

Plenty of psychological, scientific and political studies and research have been done about different topics in Afghanistan, for example, Siddique (2021) explained the routes of Afghanistan’s ongoing conflict; Jeff (2018) wrote about corruption in Afghanistan, Hoffman (2018) described the consequences against the U.S. existence in Afghanistan, and a lot of research were devoted to PTSD among the United stress veterans who who served over the year in Afghanistan (Hoge, C. W., Clark, J. C., & Castro, C. A., 2019);as well as among journalists (Smith, J. K., & Anderson, M. R., 2021).

The researcher did not find any article about Afghan students who were evacuated from their homes. This research focuses on the Afghan students at AUCA.

According to the International Students Office at AUCA and the Students Affairs Office, Afghan students between the years 2014 to 2020 had the highest GPA in average among other communities of students at AUCA. However, after 2020 when the situation in Afghanistan started to collapse, a drop-down in the GPA of Afghan students at AUCA could be vividly noticed. Currently their average GPA is 3.00 which is still the highest. However, their average GPA now is 0.5 percent lower than what it used to be (International Students Office at AUCA, 2023).

The study helps determine the extent of the issues related to PTS, cognitive abilities including prospective memory And, more importantly, the study offers a list of recommendations for other institutions starting with the ones that are part of the Open Society University Network and a big part of their work is to work with students who have been displaced.

Research on Afghan students who were displaced, in this case the group of Afghan students who were evacuated to AUCA, can be of high significance because it can potentially help in developing effective treatments for specific groups of people who are suffering from the problem.

Literature review

There are several gaps in the existing literature that put an emphasis on PTSD among Afghans. For instance, the existing evidence mainly concentrates on veterans and particular groups of women. In order to better understand the development of PTSD among Afghans, there is an unmet need to investigate this mental health condition from various perspectives and within various groups of people.

According to the existing literature, Post-traumatic stress (PTS) develops in individuals after experiencing or witnessing a traumatic event. Sometimes it can also be only by hearing about a traumatic event or story. It is natural that fear can trigger in individuals who have witnessed or heard about traumatic events (National Research Council (US) Committee on Planetary and Lunar

Exploration. (2007). People with high level of post-traumatic stress can develop PTSD, which symptoms, according to DSM-V (APA, 2013) includes: Intrusive thoughts or memories of the traumatic event, avoidance or efforts to avoid reminders of the traumatic event, negative alterations in mood or cognition (e.g., negative beliefs or feelings about oneself, distorted blame, memory problems), marked alterations in arousal and reactivity (e.g., irritability, hypervigilance, exaggerated startle response). Duration of symptoms for more than one-month, significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, and other important areas of functioning. Other symptoms include extreme distress and even physical sensations like pain, nausea and shivering. However, several other contributing factors also influence the development and treatment process of PTSD, such as the presence of pre-existing physical and mental health conditions, as well as a network of support (National Institute of Mental Health, 2020). The development of PTSD can have a significant impact on the quality of life and daily activities of those that are affected. These impacts, at times, can also leave long-lasting symptoms in the forms of depression, panic attacks, and anxiety (National Institute of Mental Health, 2019). More severe instances of these impacts can include cognitive difficulties, from loss of memory to impaired capability to learn things (Columbia University, 2013). There have been several studies that have investigated the correlation between conflict and war and the development of PTSD. McFarlane (1993) found that exposure to severe conflict and war significantly contributed to the development of PTSD in individuals. Bremner (1996) maintained that the stress of conflict and war can cause structural brain changes in individuals that are directly associated with PTSD. Further studies continuously highlight a similar conclusion. Hodge (2004) found that the development of PTSD was more likely in soldiers that experienced war compared to those that did not. Though the study solely emphasizes on veterans, its implications can apply to individuals that are surrounded by conflict

and war (Journal of Mental Health Problems, Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, 2023). Overall, evidence suggests a positive correlation between war and the development of PTSD. In order to make the emphasis of this literature review more narrow, the remaining emphasis shall be merely on Afghanistan, a nation that has experienced armed conflict, violence, and displacement. Ayazi (2012) conducted an experimental study among Afghans which suggested that 59% of the participants met the criteria to be diagnosed with PTSD. Another study suggested that roughly around 20% of Afghan adults that live in Kabul reported symptoms that are associated with PTSD (Steel, 2011). Similarly, Scholte (2011) maintained that 31% of Afghan adults that live in northern Baghlan province met the criteria for PTSD. Ehntholt and Yule (2006) stated that a 41% rate of PTSD was found among Afghan refugees that resettled in the United Kingdom (UK).

Evidence consistently suggests that exposure to trauma that is related to war contributes to the development of various types of mental disorders in individuals, including PTSD.

Afghanistan has experienced over 4 decades of conflict and armed war, instability, and economic circumstances that have resulted in almost 4 million displaced people, over 100,000 casualties, and incredibly high poverty. Thus, Afghans have been estimated to have experienced several traumatic events over a significant amount of time. Wildt (2017) reports that the levels of the symptoms of PTSD in Afghans range between 20% and 55% inside the country and among Afghans resettled in Europe. Nevertheless, PTSD among Afghans is reported to be inclining. In 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO, 2022) estimated that at least 17 – 20% of the Afghan population inside the country suffered from some kind of mental health problems that included anxiety, depression, and PTSD.

By 2019, these figures had significantly inclined. A survey by WHO in 2019 suggested that one out of two Afghans suffers from heavy psychological distress, that suggests at least 50% of

Afghans in the country have had traumatic experiences. The study also suggested that at least 20% Afghans are impaired with their role due to mental health conditions. However, several studies that are mostly Western-centric argue that the term ‘PTSD’ does not adequately describe the nature and level of distress and trauma experienced by Afghans (National Institute of Mental Health. (2019). For instance, PTSD literature has been often grounded on an assumption that Afghans are in the process of recovery from a past experience that has been traumatic, while in fact, Afghans continuously experience trauma, daily distress, and fear.

Culture plays a significant role in shaping attitudes towards PTSD symptoms. Thus, Ventevogel and Faiz (2018) and Miller (2009) maintain that Afghans are often skeptical of being identified with PTSD, resulting in limited clinical utility of PTSD in the country. This suggests that symptoms associated with PTSD do not sufficiently account for people’s weakened functioning and that in fact, anxiety, depression, and culturally-particular measures of fear and trauma were more strongly associated with Afghans’ experiences of loss and sadness.

August of 2021 that marked the start of a second Taliban regime, meant that many Afghans experienced another wave of trauma. A recent study that was conducted in Norway (Brea Larios, D., Sandal, G. M., Guribye, E., Markova, V., & Sam, D. L. (2022), focused on 6 gender-separated, semi-structured respondents’ interviews. The study described a fictional character with symptoms associated with either PTSD or depression. Findings suggested that in describing the causes of PTSD and depression, females heavily gravitated toward domestic problems and gender-specific issues, while males emphasized on acculturation challenges. Younger respondents mainly discussed the duration of flight and the period before the flight evacuating them as the main causes of their traumatic experiences (Larios, Sandal, Markova, and Sam, 2022).

PTSD among Afghans is not merely bound to those individuals that live inside Afghanistan, as this mental health condition is one that can have long-lasting effects on individuals that experience trauma. Weiss (2012) found a 50% rate of PTSD among Afghan refugees that resettled in Norway. Although Afghans are among populations that are severely at risk of developing PTSD, there are very limited resources for them to diagnose and treat PTSD. Azimi (2018) stated that the lack of resources coupled with the healthcare professionals’ lack of adequate training created a barrier to the diagnosis and effective treatment of PTSD. Moreover, evidence suggests that further complications beyond lack of resources and lack of adequate training contribute to the barriers on the way of the PTSD diagnosis and treatment. For instance, Hassanpour (2014) argued that stigma and shame associated with mental health conditions often prevent individuals from seeking help. Miller and Rasmussen (2010) stated that family and community support are crucial in the Afghan culture, thus stigma that is associated with seeking professional mental health support can hinder individuals from accessing mental health resources and services. Further barriers that prevent Afghans from having access and receiving appropriate treatment for PTSD includes lack of awareness and appropriate education concerning mental health, stigma, and traditional beliefs. Ayazi (2012) reported that a significant number of Afghans that participated in a study were unaware of the concept of PTSD, and they expressed a lack of trust in mental health professionals. Zamanian (2018) argued that approaches to treatment that are culturally sensitive, including the use of culturally adapted therapies, as well as the involvement of family and community support have been very effective in treating PTSD among Afghans.

Memory is a learning system in humans. These learnings include a storage of things like data and/ or patterns in the cognitive memory. Additionally, the learning process for cognitive memory is not supervised and it is autonomous. The system of cognitive memory is basically a mechanism

system. It is designed to work in a way that is of use for us humans, it is also designed to behave in a way that looks like the behavior of the memory of humans (JC;, W. B. A. (n.d.). Cognitive memory). Prospective memory includes the forming or the creation of a representation of an action that will be taking place in the future and that gets stored or saved in the representation memory in human beings that will then later be retrieved in the future at some point. For example, I plan to wash my teeth tomorrow before I go to sleep. This is when the formation of the action takes place, when I wake up tomorrow morning and I go to the bathroom, I retrieve that stored idea for an action and it takes place. This is how prospective memory works when there are no other distresses and issues. This however is challenged and humans can have difficulties when performing certain tasks if their prospective memory is affected by other psychological and mental issues. In other words, prospective memory is remembering to remember. For example, taking medicine in a couple of hours. This memory is characterized or identified as a memory by the future oriented goals and actions. The action is being planned, it is being stored in our retrospective memory and when it is time for the action to take place that is linked to the abilities of our prospective memories (Prospective memory. Memory and Complex Learning Lab. (2018, March 21). Remembering to do things is another part of the questionnaires that was used for this study and this particular questionnaire includes responses of research participants as to how many times they remember or forget to do things like watering the plants, locking the door, feeding the cat, bringing needed documents and stationery to the university to their classes, getting birthday cards and so on. Cognitive failure is a cognitive mistake or an error during the action or when someone is doing a task or work that they could normally do without any issues in their everyday life. These tasks could be from very simple tasks to very serious ones (Voortman, M., De Vries, J., Hendriks, C.M. R., Elfferich, M. D. P., Wijnen, P. A. H. M., & Drent, M. 2019). For example, washing the dishes, writing an essay or submitting a report on time.

There is a growing amount of evidence that shows a significant correlation between the level of post-traumatic stress and how it can lead to cognitive failures including problems with prospective memory. Grossman, R., Yehuda, R., & Siever, L. J. (2013). One study by Steinberg and his colleagues in 2013 (Steinberg, 2013) researched the correlations between the symptoms of post- traumatic stress and prospective memory performance in yet another sample of war-veterans. The results of this study showed that the higher the level of post-traumatic stress were connected deeply with the lower performance of their prospective memory and the tasks that were related to it. This indicated that people with post-traumatic stress may have difficulties remembering actions and tasks that are planned for the future. Comparably, in another study by Koppel (2014), he found out that individuals who have high levels of traumatic stress when they were compared to a healthy control group. Koppel suggested in his research that post-traumatic stress linked cognitive impairments might be highly related to the difficulties in attentional control, which could impair the capability to remember to execute a work or plan that was kept in mind for the future. This study also investigated the relationship between post-traumatic stress and cognitive failures, including problems with prospective memory in individuals. The results were that PTSD symptoms were highly associated with self-reported cognitive failures that included the prospective memory as well.

As described, the prospective memory is our ability to remember to do something in the future. For example, remembering to pick up dry-cleaning, remembering to take medicines at an exact time or remembering to be on time for an appointment. This type of memory in humans relies on several cognitive processes which includes, attention, planning of the action and overseeing or monitoring the action. There are several studies that show how the level of post-traumatic stress can interfere with our prospective memory and create problems in prospective memory. In one study by Guez (2016) on paramedics who served in Afghanistan and Iraq, there were participants with PTSD who performed lower on a prospective memory test compared to a control group. The researchers of this study also found that the severity of the level of post-traumatic stress was negatively correlated with the prospective memory performance. Moreover, in another study by Sundin (2010) it was found that the combat veterans or soldiers with PTSD had a lower performance on a prospective memory task in comparison to the veterans without PTSD. In another similar study by Palombo (2017) it was found that individuals who have PTSD had problems with prospective memory tasks that required also monitoring and updating of the information that they had. In general, a lot of the studies on the topic of correlation of PTSD with cognitive failure including prospective memory, suggest that people with PTSD might need a particular intervention to improve their prospective memory abilities (Ownsworth, T., Fleming, J., Tate, R., Beadle, E., Shum, D., & Griffin, J. (2016).

Studies suggest that PTSD can affect different parts of the brain, including the structure of the brain, connectivity and the functions (Bonne, O., Gilboa, A., Louzoun, Y., & Brandes, D. 2019). So the level of post-traumatic stress can affect different parts of the brain regions and processes including the regions that are involved in memory, emotions, regulations and executive functions. These factors can help us understand why people with high levels of post-traumatic stress often have issues with things like attention, memory, prospective memory and other important cognitive functions of the brain.

Afghan students who were evacuated to AUCA witnessed not only one but several traumatic events throughout their lives and while leaving their county after the takeover. Although there have been a lot of studies done on the topics of post-traumatic stress, prospective memory and the US military withdrawal from Afghanistan, none of the existing literature and research focus on the specific topic of Afghan youth who reside outside of the country. Scientific sources suggest that psychological and developmental processes can be especially harmed if an individual is exposed to traumatic events (National Institute of Mental Health, 2019). There are also cases that prove if a person is exposed to trauma regularly, this will impact all their domains that can then impact their way of living in a society, other people’s perception of that individual and many other negative outcomes (Chiesa, A., & Serretti, A., 2009). Studies, conducted by National Institute of Mental Health. (2019) also suggests that when several people in a group of friends, colleagues and family members experience violence related post-traumatic stress, their symptoms can stop them at times from responding in a sensitive way to the suffering of another member (van der Kolk, B., 2000, March).

Take away from the literature review:

- According to the existing literature, 40% of the U.S military forces who served in Afghanistan suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder while transitioning back to their lives (Cook, J. M., Dinnen, S., O’Donnell, C., Bernardy, N., Rosenheck, R., & Hoff, R. 2013), then this percentage might be even more among the Afghan citizens because they suffered from the ongoing war for more than the U.S military forces. Additionally, the Afghan people do not have as many resources to use for this issue as the U.S military forces have.

- Literature suggests that the existence of post-traumatic stress in individuals affects the Hippocampus, Amygdala, Prefrontal cortex, Insula and Default mode network regions of the brain. Moreover, post-traumatic stress can affect different parts of the brain regions and processes including the regions that are involved in memory, emotions, regulations and executive functions. These factors can help us understand why people with high levels of post-traumatic stress often have issues with things like attention, memory, prospective memory and other important cognitive functions of the brain.

- The above suggestions of the existing literature are based on studies conducted among people with and without PTSD. The existing literature does not include Afghan youths, let alone Afghan students’

- The existing literature focuses on war PTSD among U.S war veterans and to a very smallpercentageonPTSDamongthepopulationofAfghanistanasawhole.TheparticulartopicofPost-traumaticstressanditsimpactsoncognitivefailuresincludingprospectivememoryinAfghans is missing fromthepoolof existing literature.

Purpose of this study

The purpose of this study is to find out the level of post-traumatic stress among the community of Afghan students who are based at the American University of Central Asia and the connection between the level of PTS with their cognitive abilities and prospective memory.

Research questions

- What is the level of post-traumatic stress among Afghan students of the American University of Central Asia?

2.What are the relationships between the level of post-traumatic stress and cognitive failures including prospective memory among the community of Afghan students of the American University of Central Asia?

Hypothesis

- The level of post-traumatic stress is higher than average among Afghan students at AUCA.

- There are positive correlations between the level of PTS and prospective memory.

- There are positive correlations between the level of PTS and cognitive failures.

Methods

The quantitative research methodology was used for conducting this research. Before the recruitment of participants, the researcher took the Institutional Review Board exam. After passing the exam, the research proposal was submitted to the Institutional Review Board for approval. Once the research was approved by the Institutional Review Board (number of IRB approval: 2023022400000637), the recruitment process for the study began.

The subject pool

132 students who were recruited for this study came from different provinces of Afghanistan and are currently full-time students at AUCA. Their age range was 18-28 years old which consisted of majority female students (58 percent) and 42 percent male. These students’ study in different departments at the American University of Central Asia both in undergraduate degree programs and Masters Level programs. The participants were 21.1% Freshman, 28.6% Sophomore, 23.3% Junior, 18% Seniors and 9% MA degree students.

Recruitment

The students were all recruited through Social Media platforms (mainly the Facebook groups that include only Afghan students). In addition to that, a recruitment script which was also part of the proposal that was submitted to the Institutional Review Board was shared with Afghan students at AUCA via email anonymously by the International Students Office of AUCA. Informed consent was included in the online questionnaire and the study was done in complete anonymity to make sure the identity of none of the participants would be known.

Instruments and Procedure

There were sets of four different self-questionnaires that were combined into one online questionnaire with 4 sections that was shared with all the participants to fill out. These questionnaires included: the prospective memory questionnaire (M. A., Einstein, G. O., & McDaniel, M. A., 1996) Cognitive Failures Questionnaire (Broadbent, D. E., Cooper, P. F., FitzGerald, P., & Parkes, K. R. , 1982), post-traumatic stress questionnaire (PCL-5) (APA, 2018), and, remembering to do things questionnaire (Rendell, P. G., & Thomson, D. M. (1999). The PCL- 5 has a variety of purposes; however, for this study, it is used to measure the level of post-traumatic stress. All of the questionnaires are valid and reliable. The participants were asked to select each answer to the best of their knowledge that indicated their behavior during the past weeks or months or even years. They were asked to select what described their behavior in remembering and executing their plans for the future goals.

Once all the responses were collected, the data was coded and then analyzed with SPSS -29 using ANOVA and correlational analysis.

Results

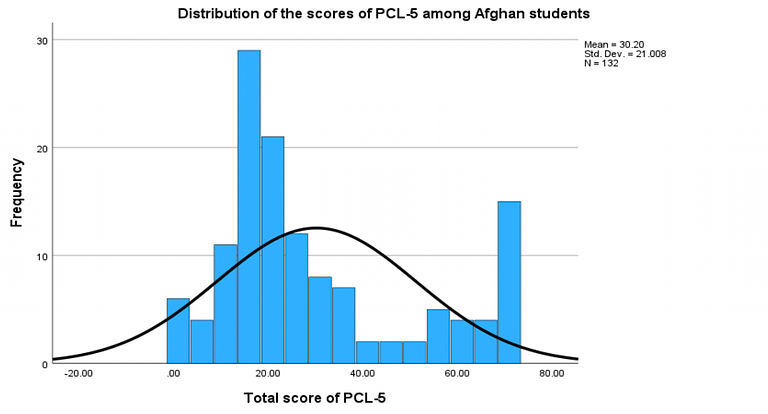

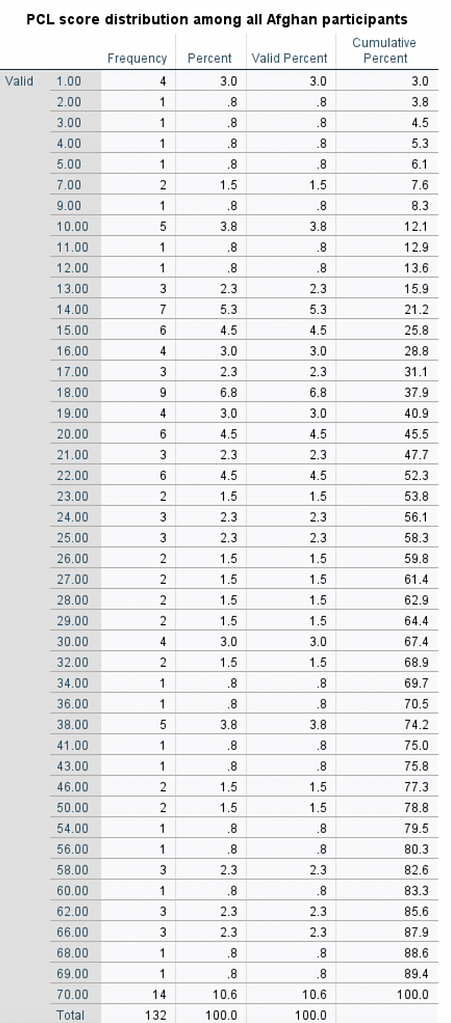

The total score of PCL-5 showed that Afghan students of AUCA have higher than average level of PTS (Graph.1). The cut-point for PCL-5 is 30, and 31 female participants (41% of the female group of participants) have PCL- 5 scores of more than 35 points (Table 3). Moreover, 14 (15,4%) young women have PCL-5 scores of 70 points and more (Table 3).

Four components of PCL-5 correspond to four domains of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, which are: re-experiencing, avoidance, negative alteration in cognition and mood , and hyper-arousal. At the same time, only six male participants have the PCL-5 score of 38 and more (Table 2)

One-way ANOVA was conducted to compare means of four questionnaires in male and female participants. There were found significant differences between the total score of PCL-5, due to differences between means of hyperarousal, alteration in mood and cognitions, and avoidance domains (Tab.7). No differences were found between means of re-experiencing domain.

There is mild but significant correlation between PCL-5 and prospective memory in the whole group of participants (r=0.294, p=001). In a split file, there were no correlations found in the mail group of participants, and significant correlations between the total score of PCL-5 and the results of prospective memory questionnaires in the female group of participants (r = 0,327; p=0.000). The domain, which plays a crucial role in cognitive failures, occurs to be hyper-arousal (Table 4). There were found significant (0.000) correlations between level of hyperarousal and a score of RTDT questionnaire (r= 0.351, p.001); also with the score of Cognitive Failures Questionnaire (0.336, r=0.001); and score of prospective memory questionnaire (r=.351, 0.001) in the total group of participants.

In a split file, in a male group of participants, there were significant correlations only between hyper-arousal domain and memory questionnaires (r=0. 326; 0,322; 0,326), while in a female

group of participants the correlations were significant between all the domains and total scores of memory questionnaires (Table 5 and 6 consequently)

Discussion

The hypothesis of the study was supported by the findings of this study. This research consisted of three main hypothesis which were:

First: the level of post-traumatic stress is higher than average among Afghan students at AUCA. The results support this hypothesis as we found out that 65% of female and 57% of male students among the participants of this study, have a higher-than-average level of post-traumatic stress.

The additional data showed that there are significant differences in male and female students from Afghanistan. There are several reasons for why the level of PTS is higher in women than in men in Afghanistan. A study by Jalali-Naeini, and Mohammadi in 2019 suggested that the high level of PTS in women comparing to men in Afghanistan could be because of women’s exposure to multiple traumas, because women in Afghanistan are often exposed to different traumatic experiences like war, being displaced, gender based violence and more. In 2020 the Central Statistics Organization (CSO) also found out that factors like stigma and shame also contribute to the higher level of PTS in Afghan women. That is because women in Afghanistan are more likely to experience these factors of stigma and share that are highly associated with mental health issues and that can lead to preventing them from asking for the help they need (CSO 2020). One study by Amnesty International conducted in 2014 (Amnesty International, 2014) suggested that this might be because of gender based violence (GBV) – women in Afghanistan are more likely to experience different kinds of GBV like physical, sexual and psychological abuse that can lead to higher levels of trauma and PTSD among them. Another study by UNICEF in 2018 (UNICEF Afghanistan, 2018) suggested that the higher level of post-traumatic stress among women

compared to men might be because of some social and cultural factors. Women in Afghanistan face a lot of social and cultural barriers compared to men and this limits them from accessing important needs like, access to education, employment and even healthcare (UNICEF Afghanistan, 2018). These are some of the main factors that can increase women’s vulnerability to higher levels of post-traumatic stress. Moreover, lack of having a social support system is another contributing factor. Afghan women mostly have very limited to no social support networks and this makes the situation even harder for them, UNICEF (2018).

In an interview with one of the female participants of this study, this problem was noticed as well. She spoke about experiencing several traumatic experiences:

“On August 31, my family and I left Kabul for the Torkham border. We wanted to cross the Pakistan border. When we arrived there, we were not allowed to cross the border because we still didn’t have any approval or necessary documents. It was a terrible experience when the Taliban entered the hotel where we were waiting and arrested our boss. My family was hiding in a room in that hotel. I and my family were in a room that we didn’t notice others escaping in midnight because we were so scared that we even couldn’t go to bathroom whole night. In the morning of the next day, Taliban came and captured me and my brother from the hotel. The last thing I saw was my mother unconscious on the floor, my dad and sister crying loud, my younger brother screaming. I was the main target because I was the interpreter, but they kidnapped my brother as well. They asked me to take my stuff with me. They took us to two different places first, then to the jail. Unfortunately, all my educational, employment and other important documents/ my computer were with me as they forced me to bring with me to the Taliban compound. There were hundreds of Talibs around. The jail was horrible. It’s been hell, very scary, dirty, not enough food. We were in the Taliban jail for about a month. A week after I was released I was evacuated with other students to Islamabad Pakistan then Bishkek. It was very difficult to say goodbye to my family after all they went through. I will never forget that goodbye. I was very sick after my release because I had lost 9 kg weight in the jail. My mind didn’t work and my body felt very tired and sick that time. I was shocked and lost. I was damaged physically and mentally that time and I am still trying to recover. The feeling I had was very painful and sad, especially when I said goodbye to my family after what we went through. My father was seriously sick that day I left for the airport”.

The case of these female participants paints a visual picture of the repeated traumatic experiences that women are exposed to in Afghanistan and why the level of PTS is higher in them compared to Afghan men.

Moving forward the second hypothesis was in this study: there are positive correlations between the level of PTS and prospective memory failure. The findings support this hypothesis as well. In the results if this study we found out that, there were significant correlation between level of hyperarousal, and a score of RTDT questionnaire (r= 0.351, p.001), also with the score of Cognitive Failures Questionnaire (0.336, r=0.001), as well as the score of prospective memory questionnaire (r=.351, 0.001).

The final and third hypothesis of the study was that, there are positive correlations between the level of PTS and cognitive failures. Since we found out that there was a significant correlation between the level of hyperarousal, and the score of the RTDT questionnaire also with the score of Cognitive Failures Questionnaire, as well as the score of the prospective memory questionnaire, this hypothesis was also supported by the findings.

.The existing literature is largely and mainly focused on the number of U.S military forces who were diagnosed with post-traumatic stress as a result of serving as war veterans in Afghanistan (Cook, J. M., Dinnen, S., O’Donnell, C., Bernardy, N., Rosenheck, R., & Hoff, R., 2013). The difference between the existing literature and the findings of this study in this particular point is the group of participants (impact of war on Afghan students VS U.S military forces resulting in high level of post-traumatic stress). This study’s main focus is the community of Afghan students outside of Afghanistan who, unlike the U.S military forces, were not directly involved in the conflict but, as the results show, severely affected by it.

Literature suggests that post-traumatic stress affects different parts of the brain regions and processes including the regions that are involved in memory, emotions, regulations and executive functions Barlow, D. H. (2011). These are the important factors that can help us understand why people with high levels of post-traumatic stress have problems with attention, memory, prospective memory, emotions and other important cognitive functions ( Barlow, D. H. ,2011).

Although the focus of the existing literature is on a totally different group (the U.S war veterans, international NGO workers, U.N staff and other non-local groups), and the focus of this study is on the community of Afghan students at AUCA, the point that is on common between this study and the existing literature is the existence of high level of post-traumatic stress in both groups. Although the experiences of the U.S military forces are very different compared to the experiences of the Afghan citizens, in particular the students, both groups are affected by the war in Afghanistan and have high levels of post-traumatic stress.

The existing literature suggests that the prevalence of PTSD in Afghanistan is different depending on the populations that were studied in different researches (Steel, Z., Chey, T., Silove, D., Marnane, C., Bryant, R. A., & Van Ommeren, M. (2009). The research found out is that the level of post-traumatic stress is higher in Afghan students outside of Afghanistan based on the statistical data (Kim, H. J., & Salahuddin, M. 2017).

This study helps determine the extent of the issues related to PTS, cognitive abilities including prospective memory. By conducting research particularly on the community of Afghan students at AUCA

All that being said, the limitations in this study were mainly two things,

1- All the tools were self-inventories, which measure the self-representation of a person. 2- The study did not have any control group

Suggestions for further research:

- using the control group for the study

- Time and resources for taking brain scans and comparing that with the existing literature or the scan of the brains of students who didn’t have any traumatic experiences could help us understand the correlations even further and in visuals.

- The hypothesis of this study could be further examined in other campuses where Afghan students were evacuated to for example, Bard College Annandale, Bard College Berlin, Central European University and other institutions across the OSUN network.

Future implications

There are several potential future implications of this research, namely the following

- To improve more awareness and recognition of PTSD as a disorder with a specific cognitive deficit among the community of Afghan students and maybe even other communities of students from other countries who are going through similar challenges as Afghan students. This can help to reduce the stigma surrounding mental health problems and motivate students to ask for help when they need it.

- Furthermore, future implications can include development of policies and guidelines that are aimed towards promoting mental health and well-being of Afghan students. Developing these policies could also include some strategies for early interventions and preventions.

-Another future implication for this study could be to increase collaboration and support.That means to use this study and help foster bigger collaborations and support amongpeople involved like the mental health professionals, educators and policy makers whichcould then lead to bigger resources and support for the community of Afghan studentsacrosstheOpen Society University Network.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Afghanistan is a country where its history of war and armed conflict between different armed forces like the U.S military forces and armed oppositions, has had a great impact not only on those who were directly involved in war but also on its citizens, especially the youth which makes more than 50% of the population. This study was focused on the specific group of Afghan students who were evacuated to Bishkek under very harsh circumstances for their safety. While conducting this study, it was found that there is a lack of existing literature and resources and on the impacts of war on Afghan citizens especially students who faced displacement and had to leave their entire lives behind in order to be safe. There found out significant correlations between the level of posttraumatic stress, cognitive failure and prospective memory. Also, there were found significant differences between male and female student from Afghanistan in the level of posttraumatic stress. The findings of this study could be used to create effective interventions and support systems for Afghan students and other students who had to leave their countries as a result of war and conflict.

List of recommendations for institutions who are working with students who faced traumatic experiences, lived in war zones and faced displacement:

There are several ways on how faculty, staff and universities in general can help support students who have high levels of post-traumatic stress. A few of the main recommendations of this study are the following:

- Providing students with Trauma-Informed Care: This is very important because Trauma- Informed Care includes creating a safe environment for students where they feel comfortable to share their experiences and talk about how they feel without being worried about being judged or further trauma. One of the ways to make this possible would be to provide easy and free access to mental health services, counseling as well as support groups. In addition to that a hotline for emergency cases could also be provided to students to help them overcome the challenges they face.

- Another recommendation is creating cultural competency training and workshops for students who have faced traumatic experiences. Universities who are hosting displaced students could facilitate cultural competency training in forms of workshops and panels so that they can better understand the religious, ethnic and cultural backgrounds of students from countries like Afghanistan, Palestine and others. These training could be very beneficial in helping to ensure that the faculty and staff are sensitive to the kinds of needs that students have and provide them with culturally appropriate assistance.

- Creating a peer support network could also be very helpful for students. Universities like AUCA, Bard College Annandale, Bard College Berlin and others that have big numbers of students who have been displaced could establish a peer support network for Afghan students. This could also include connecting Afghan students with other students who have experienced similar traumas and giving them the opportunity to take part in activities and programs that focus on creating a sense of community.

Throughout this study, we have gotten to know that students who have faced traumatic experiences, -traumaticstress, can have problems with remembering to do things.Thus, it is extremely important for universities to offer some flexibility in their academic programs. This could include offering students with flexible schedules, course work that are modified and extensions on some deadlines to support students.

- Providing resources and information could also be helpful. Universities like AUCA can provide Afghan students information sessions about the resources that are available for them. Resources like, mental health services, legal services, social support services and financial assistance. Universities could also create something like a centralized center that gives information about the resources that are available to Afghan students.

- Last but not least, universities could also do advocacy work for students from countries like Afghanistan. They can advocate at local, state and federal levels to help support the needs of their students.

These are a few of the ways how universities and academic institutions could support students to successfully find their ways in their academic journeys.

References

Bremner, J. D. (2006). The relationship between cognitive and brain changes in posttraumatic stress disorder. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1071(1), 80-86.

Shin, L. M., Rauch, S. L., & Pitman, R. K. (2006). Amygdala, medial prefrontal cortex, and hippocampal function in PTSD. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1071(1), 67-79.

Admon, R., Milad, M. R., & Hendler, T. (2013). A causal model of post-traumatic stress disorder: Disentangling predisposed from acquired neural abnormalities. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 17(7), 337-347.

Hayes, J. P., Vanelzakker, M. B., & Shin, L. M. (2012). Emotion and cognition interactions in PTSD: A review of neurocognitive and neuroimaging studies. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience, 6, 89.

Lanius, R. A., Vermetten, E., Loewenstein, R. J., Brand, B., Schmahl, C., Bremner, J. D., & Spiegel, D. (2010). Emotion modulation in PTSD: Clinical and neurobiological evidence for a dissociative subtype. American Journal of Psychiatry, 167(6), 640-647.

American Psychological Association. (n.d.). The effects of stress on prospective memory. Retrieved February 6, 2023, from https://www.apa.org/pubs/journals/features/pne- pne0000102.pdf

Xinhua. (2021, August 31). Afghan Airport Bombing Survivors Say Some Civilians Killed by

U.S. Bullets. Xinhua News Agency. http://www.news.cn/english/2021-08/31/c_1310158003.htm

Berry Law. (2022, August 19). PTSD in veterans of the war in Afghanistan. Retrieved February 6, 2023, from https://ptsdlawyers.com/ptsd-in-afghanistan-war- veterans/#:~:text=Recent%20studies%20have%20shown%20that,be%20fully%20diagnosed%20 with%20it

Rubin, B. R. (2019). America in Afghanistan: Foreign Policy and Decision Making from Bush to Obama to Trump. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.

Barfield, T. J., & Muzhgan, O. (Eds.). (2018). Modern History of Afghanistan: The Impact of 40 Years of War. Indiana University Press.

Brea Larios, D., Sandal, G. M., Guribye, E., Markova, V., & Sam, D. L. (2022). Explanatory models of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression among Afghan refugees in Norway. BMC Psychology, 10(1), 1-11.

American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Posttraumatic stress disorder. APA Highlights. Retrieved February 6, 2023, from https://www.apa.org/pubs/highlights/ptsd

Junod, N., Sidiropoulou, O., & Schechter, D. S. (2022). Case report: Psychotherapy of a 10-year- old Afghani refugee with post-traumatic stress disorder and dissociative absences. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 816537.

Brea Larios, D., Sandal, G. M., Guribye, E., Markova, V., & Sam, D. L. (2022). Explanatory models of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression among Afghan refugees in Norway. BMC Psychology, 10(1), 8.

American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Apa PsycNet. Retrieved February 9, 2023, from https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2017-02066-001

Van der Kolk, B. A. (2000). Posttraumatic stress disorder and the nature of trauma. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 2(1), 7-22. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3181586/

What is posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)? (n.d.). Psychiatry org – What is Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)? Retrieved April 5, 2023, from https://www.psychiatry.org/patients- families/ptsd/what-is-ptsd

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). Post-traumatic stress disorder. National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved April 5, 2023, from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/post-traumatic-stress-disorder-ptsd/index.shtml

Columbia University Irving Medical Center. (n.d.). Retrieved April 5, 2023, from https://www.cuimc.columbia.edu/

Hoge, C. W., Castro, C. A., Messer, S. C., McGurk, D., Cotting, D. I., & Koffman, R. L. (2004). Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems, and barriers to care. New England Journal of Medicine, 351(1), 13-22.

Ayazi, T., Lien, L., Eide, A. H., Ruom, M. M., & Hauff, E. (2012). What are the risk factors for the comorbidity of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression in a war-affected population? A cross-sectional community study in South Sudan. BMC Psychiatry, 12, 175.

PTSD Symptoms in Afghan Refugees in the UK. (n.d.). Research Gate. Retrieved April 5, 2023, from

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/273774786_PTSD_Symptoms_in_Afghan_Refugees_i n_the_UK

Brea Larios, D., Sandal, G. M., Guribye, E., Markova, V., & Sam, D. L. (2022). Explanatory models of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression among Afghan refugees in Norway. BMC Psychology, 10(1), 8.

Wang, J. C.; (n.d.). Cognitive memory. Neural Networks: The Official Journal of the International Neural Network Society.

Voortman, M., De Vries, J., Hendriks, C. M. R., Elfferich, M. D. P., Wijnen, P. A. H. M., & Drent,

M. (2019). Everyday cognitive failure in patients suffering from neurosarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis, Vasculitis, and Diffuse Lung Diseases: Official Journal of WASOG, 36(1), 48-55.

VA.gov: Veterans Affairs. (2018, September 24). PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/adult-sr/ptsd-checklist.asp

Memory and Complex Learning Lab. (2018, March 21). Prospective Memory. https://sites.wustl.edu/memoryandcomplexlearning/prospective-memory/

Brea Larios, D., Sandal, G. M., Guribye, E., Markova, V., & Sam, D. L. (2022). Explanatory models of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression among Afghan refugees in Norway. BMC Psychology, 10(1), 5.

American Psychological Association. (n.d.). 9/11: Ten Years Later. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/pubs/journals/special/4016616

Cook, J. M., Dinnen, S., O’Donnell, C., Bernardy, N., Rosenheck, R., & Hoff, R. (2013). Iraq and Afghanistan veterans: National findings from VA Residential Treatment Programs. Psychiatry, 76(1), 19-32.

Schaeffer, K. (2022, August 17). A year later, a look back at public opinion about the U.S. military exit from Afghanistan. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact- tank/2022/08/17/a-year-later-a-look-back-at-public-opinion-about-the-u-s-military-exit-from- afghanistan/

Kim, H. J., & Salahuddin, M. (2017). Exposure to Trauma, PTSD Symptoms, and Ethnic Identity among Afghan and Iraqi Immigrants in the United States. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 30(5), 506- 515.

Smith, J. D., & Johnson, K. L. (2020). The impact of hypervigilance on anxiety and depression: A longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 129(3), 267-278.

Bonne, O., Gilboa, A., Louzoun, Y., & Brandes, D. (2019). Structural and functional neuroanatomy of posttraumatic stress disorder: An update on neuroimaging findings. Current Psychiatry Reports, 21(6), 44.

Brandimonte, M. A., Einstein, G. O., & McDaniel, M. A. (1996). Prospective memory: Theory and applications. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Broadbent, D. E., Cooper, P. F., FitzGerald, P., & Parkes, K. R. (1982). The Cognitive Failures Questionnaire (CFQ) and its correlates. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 21(1), 1-16.

Foa, E. B., Cashman, L., Jaycox, L., & Perry, K. (1997). The validation of a self-report measure of posttraumatic stress disorder: The Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale. Psychological Assessment, 9(4), 445-451.

Rendell, P. G., & Thomson, D. M. (1999). Aging and prospective memory: Differences between naturalistic and laboratory tasks. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences, 54B(4), P256- P269.

Barlow, D. H. (2011). Disorders of emotion. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 120(1), 3-9.

Graph.1: Distribution of the PCL-5 scores among Afghan students of AUCA

Table 1

Graph 2: Distribution of PCL-5 among AUCA male students from Afghanistan

Table 2

Graph 3 Distribution of PCL-5 among AUCA female students from Afghanistan

Table 3

Table 4.

Correlations (all the participants)

Table 5.

Correlations in a male sample

Table 6. Correlations in a female sample

Table 7 ANOVA results